New app can help improve public transport

Scroll ned for at læse mere

Scroll ned for at læse mere

By Christina Tækker, DTU

When the first self-driving shuttles start running at the DTU Lyngby Campus in summer 2020, about 500 test passengers will have installed a LINC app developed by DTU in collaboration with Roskilde University and IBM.

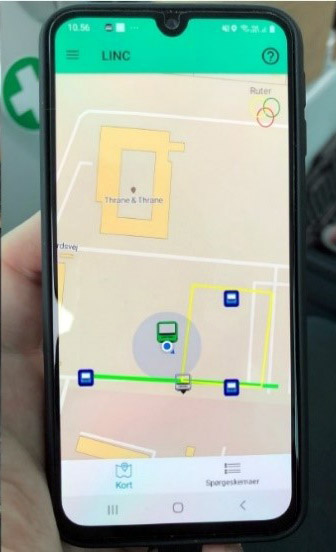

Using the app, test passengers can see the self-driving shuttles’ current locations and when they are in operation. At the same time, researchers can use the app to collect data on the behavior and movement patterns of test passengers in connection with their use of the shuttles.

But the unique feature of this app is that it combines well-known technologies from running and health apps with elements of traffic research. The app includes built-in GPS and Bluetooth beacons connected to radio transmitters, which are mounted both inside the shuttles and at the shuttle stops.

This allows you to see who is in the vehicle and when they get on or off. Additionally, researchers will use questionnaires sent to users in real time.

“We have pushed this app much further than others,” says Per Bækgaard, associate professor at DTU Compute. “It’s not just a tracking app, where we can see how many people have taken the self-driving shuttle. We can also use it as a tool and integrate it with a questionnaire. Using Bluetooth beacons, we can analyze data more accurately while passengers are inside the shuttle. Hopefully this will give us an even more detailed insight into their transport patterns.”

Presently, DTU researchers are collaborating with IBM to identify the situations that can provide the best data to map passenger transport patterns. The data may include how many passengers are on the bus, how many are at a shuttle stop, how long they have been waiting and where they typically get on and off the shuttle.

They will also collect data on the typical behavior and usage patterns of test passengers. This information can be a significant input to designing optimal shuttle routes. Behavioral data can, for example, show whether users refrain from taking the self-driving shuttles if there are many passengers on board, or if they are alone on the bus, as well as how test passengers typically react if there are many people waiting at the stop compared to if they are waiting alone.

As an additional feature of the app, researchers will also gather information on how test passengers behave in relation to the weather. Will they, for example, plan a trip from home if ran is forecast for the whole day?

The plan is for all data to be analyzed on a dashboard where researchers can continuously monitor how the shuttles are used. If one of the shuttles suddenly stops, the researchers can, after half an hour, send a questionnaire to the passengers that were on board to ask how they experienced the unexpected stop.

“Traditional traffic research is largely based on questionnaires that are sent up to three months after using public transport. And then it can be difficult to remember each trip in detail,” says Per Bækgaard.

“We expect to receive a more accurate response from users this way. And we expect to get a higher response rate because we will be asking in a more targeted way. We also think we can get more correct answers because passengers have not had time to go through a lot of post-rationalization. If you are in the right environment when answering the questions, it is easier to remember what happened.”

The research project is limited to gathering data on the use of self-driving shuttles within DTU and focuses on the so-called “last-mile” challenge, meaning transport to and from public transport. Although the project is smaller in size, Per Bækgaard is excited to follow the usage patterns and see the accuracy of the data that is collected. The results can be transferred to public transport if the app is also tested on a larger scale:

“I think the Danish public transport system needs to be reconsidered in a number of ways. In this project, if we can better understand the movement patterns of test passengers, we can design solutions that are much better adapted to the individual needs of users. We can use these results to improve public transport – and perhaps even optimize usage – so that we do not all have to waste time in congestion on the highway.”